BY MA. NINA PAMELA CASTRO AND ANNA BIALA

For many years now, the squabble over the West Philippine Sea is a narrative of undying conflict and power struggle. Philippine economy is badly affected. Lives of fishermen are put in danger. Now that another year is coming to a close, the long dispute over the said waters is yet to be settled.

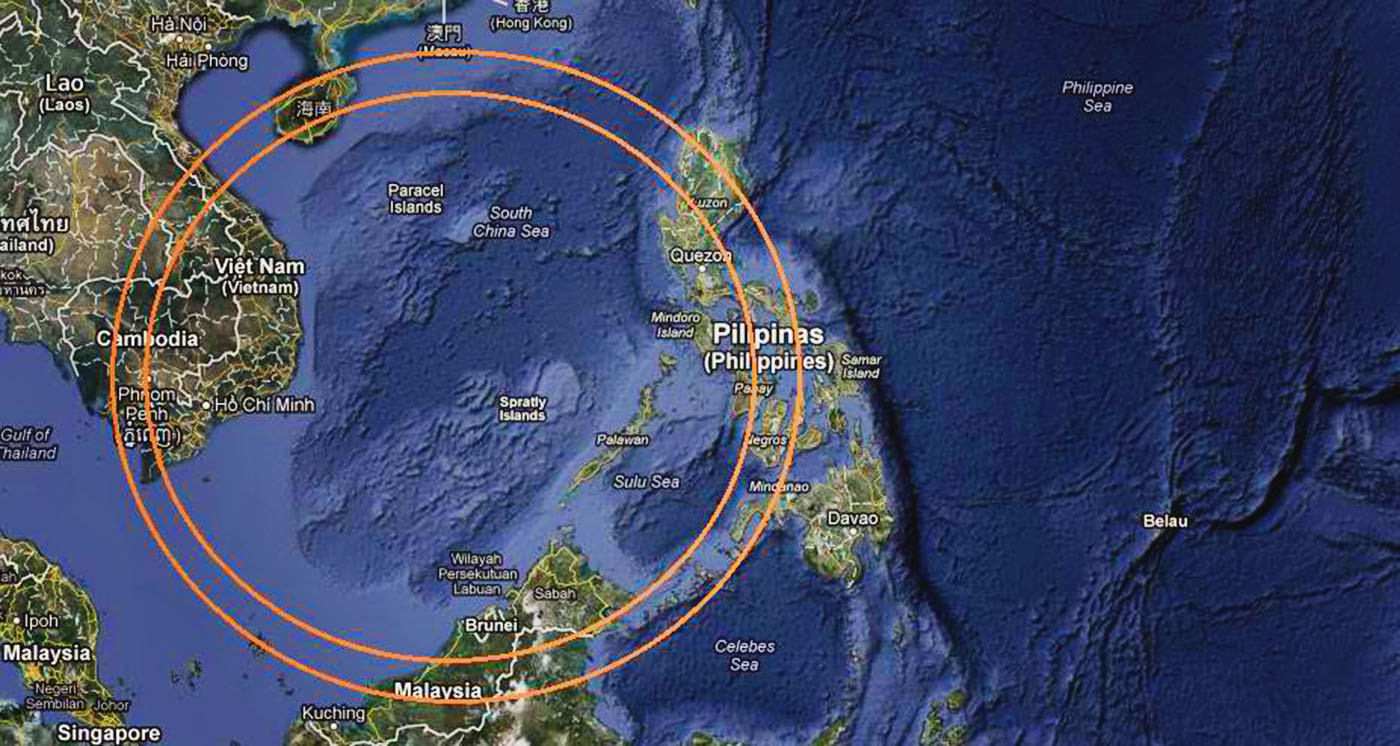

Since the 1970’s, the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries – including China, Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam – have been steadfast on their claims over the South China Sea and the islands in the region.

China asserted its territorial sovereignty through the historic “nine-dash line,” a demarcation line published initially in a map released by the Republic of China in 1947 to delineate its land reclamation on several territories.

Pentagon’s 2015 report said, “China has constructed more island surfaces than all other claimants has established throughout history.”

The squabble over the West Philippine Sea is a narrative of undying conflict and power struggle.

The “nine-dash line” was put into question when the Philippines filed an arbitration case with 15 arguments against China in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in January 2013.

“No State should be permitted to write and re-write the rules in order to justify its expansionist agenda,” Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario said after filing the arbitration case.

In fact, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced that they had “completed the relevant island and reef area reclamation project” on Spratlys last June. These projects included excavation of deep channels and construction of berthing areas to allow access for larger ships.

According to a report by Inquirer.net, China banned 16 Filipino fishermen from Cato Village, Pangasinan from their traditional fishing grounds in the Scarborough Shoal last March by using a Chinese vessel to ram their fishing boats several times.

The Scarborough Shoal is a triangular reef located in the West Philippine Sea and is considered as a rich fishing ground. It is 240 km from the coastline of Zambales and western Pangasinan and is within the 370-km exclusive economic zone of the Philippines.

“No State should be permitted to write and re-write the rules in order to justify its expansionist agenda,” Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario said.

The fishermen also narrated in the report that Chinese Coast Guard personnel drove them out of the shoal when they went there to fish, using water cannons on three separate occasions from January to February this year.

Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping “renewed its diplomatic and economic vows” with the US in his speech at the White House last September and promised “peaceful cooperation with Asian neighbors.”

Clashes and conflicts

In August 2015, United States Pacific Commander Admiral Harry Harris and Armed Forces of the Philippines chief of staff General Hernando Iriberri discussed possible strategies to counter China’s actions in the West Philippine Sea. They agreed to increase the number of military and humanitarian drills they are conducting in the area.

In an effort to challenge China’s “aggressive claims” over the area, the US sailed a guided-missile destroyer within 12-nautical miles of the artificial islands built by the Chinese in the West Philippine Sea last October. After the said activity, China said the US should “refrain from saying or doing anything provocative and act responsibly in maintaining regional peace and stability.”

In the same month, Hague court, a United Nations-backed arbitral tribunal in the Netherlands, unanimously decided it has the right to hear historic case filed by the Philippines against China over disputed areas in the West Philippine Sea, rejecting China’s “strongest” claim that the said tribunal has no right to hear the said case.

China argued “the dispute is about sovereignty over islands, therefore the standoff is territorial and not maritime, which means the tribunal would not have the authority to hear the case.”

Hague court, a United Nations-backed arbitral tribunal in the Netherlands, unanimously decided it has the right to hear historic case filed by the Philippines against China.

The tribunal court said it has the authority to hear seven of Manila’s submissions under the UNCLOS and China’s decision not to participate did not deprive the tribunal of jurisdiction.

Before the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit kicked off last November, both China and the Philippines agreed to avoid discussions regarding the sea dispute. Department of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Charles Jose said “APEC is an economic forum and it won’t be a proper venue to discuss political security issues.”

But US President Barack Obama, after meeting with President Benigno Aquino III during the summit, called on China to stop its construction and military activities in the disputed areas and endorsed the use of arbitration process to “lawfully address differences.”

“We agreed on the need for bold steps to lower tensions including pledging to halt further reclamation, new construction and militarization of disputed areas in the South China Sea,” he said.

DFA Spokesperson Charles Jose said “APEC is an economic forum and it won’t be a proper venue to discuss political security issues.”

The United States takes no position on the territorial claims of China and other Asian countries over the West Philippine Sea, but it is determined to “defend the right of free navigation” in the said area which is “a vital route for commerce and trade.”

US President Barack Obama pledged last November to allot $250 million to strengthen the naval capabilities of Japan, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam over the next two years to help the countries stand up against the excessive claims of China on the disputed sea and ensure maritime security.

Economy at stake, too

Beyond national security, China’s tightening grip over its claim on the West Philippine Sea brings economic distress to the Philippines.

The annual per capita consumption of fish and marine products in the Philippines is about 36 kilos, and more than three-fourths of total commercial and municipal fishing production had come from the rich fishing grounds of the West Philippine Sea, according to the official data obtained by Sen. Ralph Recto.

The House of Representatives estimated 20 to 25 percent of the annual fish catch of the Philippines come from the waters of Palawan and Luzon, two areas covered by the Chinese nine-dash line map.

Beyond national security, China’s tightening grip over its claim on the West Philippine Sea brings economic distress to the Philippines.

According to a Rappler report last April, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) stated “China’s reclamation in five reefs in the Spratlys has buried 311 hectares of coral reefs”. This would put fisheries sector and food security of the Philippines in danger and could result in up to P4.8 billion in lost economic benefits, according to BFAR.

As reported by The Guardian, “dredging, land reclamation and the construction of artificial islands could be swamping centuries old reefs in sediment, endangering ecosystems that play a key role in maintaining fish stocks throughout the region.”

The dispute over the West Philippine Sea is ultimately a question of how we, as a nation, stand up and fight for sovereignty.

To beat China, among other claimants, would seem impossible – what with all its financial capacity and machinery. But as what Foreign Affairs Secretary Albert del Rosario once said, “What is ours is ours.”

After all, the dispute over the West Philippine Sea is more than just a narrative of economic concerns and territorial disputes nor a battle between Davids and Goliaths. Ultimately, it is also a question of how we, as a nation, stand up and fight for sovereignty.

Header image from Inquirer.net