BY NICOLE-ANNE LAGRIMAS

It was a victory for the fight against climate change, or so it appears, when world leaders agreed to curb their countries’ greenhouse gas emissions to hold global warming at bay in a historic pact drafted in the recently concluded Paris Climate Conference.

The city of lights hosted the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held from November 30 to December 11, 2015 and attended by 36,276 participants from 198 states.

The landmark 32-page agreement mainly provides for “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 ºC above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ºC above pre-industrial levels,” which may be a leap, considering the world’s rising carbon dioxide emissions.

It was a victory for the fight against climate change, or so it appears, when world leaders agreed to curb their countries’ greenhouse gas emissions to hold global warming at bay.

Scientists say global warming by more than 2 ºC will spell far-reaching consequences: a more rapid rise in sea levels and stronger, more dangerous weather disturbances.

To achieve this, the agreement further states that the countries, formally Parties, aim to “undertake rapid reductions” in greenhouse gas emissions, but only after they have reached “global peaking.”

The U.S. and Chinese governments agreed to greatly reduce their emissions – the U.S. by 26 to 28 percent before 2005 levels by 2025, while China’s would fall after 2030 or earlier, according to a Joint Announcement made by U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping in November 2014. Similarly, the European Union forged a pact that sees their emissions down by at least 40 percent by 2030.

The Philippines, for its part, agreed to cut down its emissions by 70 percent by 2030, a commitment that may yet change depending on technical and financial support from the international community, according to a report by the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Scientists say global warming by more than 2 ºC will spell far-reaching consequences: a more rapid rise in sea levels and stronger, more dangerous weather disturbances.

Each country will employ a nationally determined contribution, which specifies the country’s action plans and accomplishments complying with the agreement, and communicate it to the COP every five years. But the legal stick seems short, as there is no penalizing mechanism for underperforming countries, the word “sanction” and “penalty” being all but barred from the document.

The Paris Agreement was met with mixed reactions. The Philippine delegation, for one, was pleased with the outcome of the grueling 12-day conference.

“Our Paris Agreement may not be as perfect as we want it to be, but it is essentially an acceptable accord,” Climate Change Commission Secretary Emmanuel de Guzman said in a statement delivered at the Closing Plenary of the conference on December 12.

After highlighting the significance of the agreement to the typhoon-prone Philippines, De Guzman, who headed the country’s delegation at the climate conference, added, “We would have wanted quantitative targets and more legally binding language and we will continue to work for these as we implement the agreement.”

Each country will employ a nationally determined contribution, and communicate it to the COP every five years. But the legal stick seems short, as there is no penalizing mechanism for underperforming countries.

The Philippine delegation, like all the other participating countries, contributed to the drafting of the agreement. Chief in its position were the 1.5 goal, a human rights language, ecosystems integrity and a nod to “climate justice,” all of which were mostly integrated into the pact’s final draft, according to the Inquirer.

Moreover, the Philippines, chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, pushed for the inclusion of a “loss and damage” provision in the final draft of the agreement, which gives further importance to actions for “averting, minimizing and addressing…the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events,” especially for developing nations, which are both more vulnerable and less capable of combatting climate change. This was a previously objected provision, as the U.S. believed it would lead to demands for compensation.

De Guzman told the Inquirer that ordinary Filipinos, especially farmers and fishermen, who are most affected by typhoons, will benefit from the agreement, as developed countries had “promised to support adaptation and mitigation programs.”

The Philippines, chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, pushed for the inclusion of a “loss and damage” provision in the final draft of the agreement.

However, not everyone is as convinced.

Nick Filmore, a Toronto-based journalist specializing in climate change issues and writing for the Al-Jazeera, called the enthusiasm over the agreement “extremely premature.” The real culprits in global warming are fossil fuels, coal, oil, he wrote, but none of these words appear in what many exalt as a “breakthrough document.”

Yet even so, coal stocks sank mere days after the forging of the Paris agreement, according to a report by Reuters. Renewable energy stocks, on the other hand, are on the rise. Fearing for his industry, Brian Ricketts, the head of the Europe’s coal lobby, said in a letter to the media that the fossil fuel trade will be hated like “slave traders” in the aftermath of the conference.

“Fossil fuels are [being] portrayed by the UN as public enemy number one. We are witnessing a power bid by people who see the democratic process as part of the problem and have worked out ways to bypass it,” Ricketts wrote, as quoted in a report by The Guardian.

The real culprits in global warming are fossil fuels, coal, oil; but none of these words appear in what many exalt as a “breakthrough document,” Nick Filmore said.

Contrary to the worldwide trend, however, the Philippine coal industry seems to be in an upswing. In July, the government approved 29 more coal-fired plants which, unless stopped, will become operational by 2020, making the country dependent to coal for at least two more decades, according to Rappler.

For all the current debate on the merits of the agreement, however, a fact remains: the international community has come a long way from the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, an international treaty providing for the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Just that an agreement was forged may be a feat, following the lack of a resolution in the Lima Climate Conference of 2014, as politics between developed and developing countries tend to hamper quicker talks, with the U.S., China and India acting as “roadblocks in past attempts to achieve climate deals,” according to a report by Time.

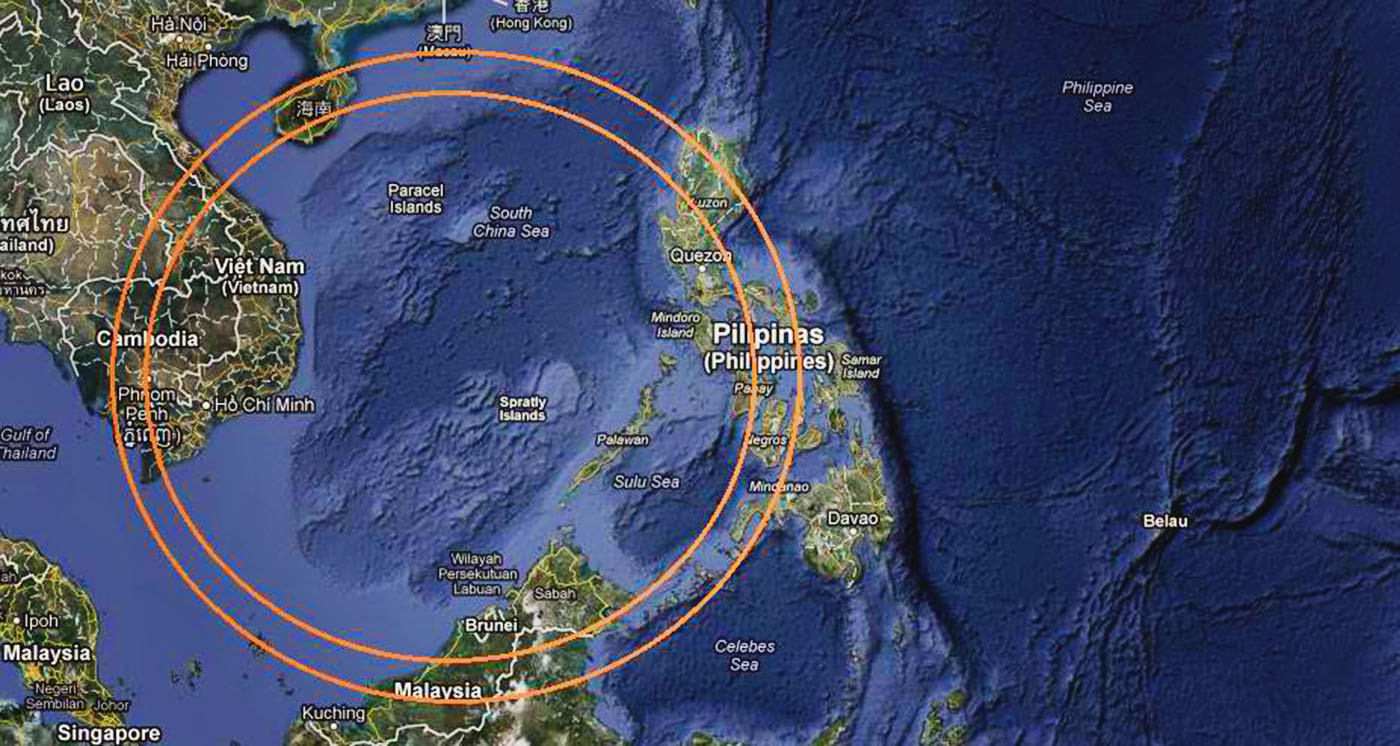

While the discussion drags on, climate change unabatedly continues to wreak havoc: melting glaciers, thus raising sea levels, forming stronger typhoons and wiping out species. The Philippines is still reeling from the damage wrought by typhoon Yolanda (international name Haiyan) two years ago even as new typhoons destroy property and lives, hence the Philippine delegation’s focus on disaster mitigation.

Just that an agreement was forged may be a feat, following the lack of a resolution in the Lima Climate Conference of 2014.

The Paris Agreement, which United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon is set to sign on April 22, 2016, is praised for its goals, but most sobering is a UN report which estimates global warming at 0.85 ºC in 2014. To stay below 2 ºC, the report states world greenhouse gas emissions have to fall to “near zero or below in 2100.”

Clearly, “lofty goals” should only be the beginning, or one might as well keep on counting the dead.

Header image from Reuters