BY DENISE VALDEZ AND SARAH MAE GALVEZ

It all started with the death of a two-year-old boy in a village in Guinea, West Africa on Dec. 6, 2013.

Emile Ouamouno of Meliandou village passed away after experiencing the symptoms of Ebola, which was not yet identified back then. The symptoms—fever, headache and diarrhea, among others—were similar and mistaken for common diseases like malaria.

Days after, his pregnant mother Sia and three-year-old sister Philomene died as well.

Because their funeral ritual involved touching, kissing, and washing, the virus quickly spread. Guests acquired and passed the virus from one place to another, until on March 23, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an Ebola outbreak in Guinea.

A week later, neighbor country Liberia announced the death of its first Ebola victim. Two months later, another border country Sierra Leone declared its first death.

Due to weak health systems, the virus spread around the three countries. And on Aug. 8 this year, the WHO declared the epidemic a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Multitude

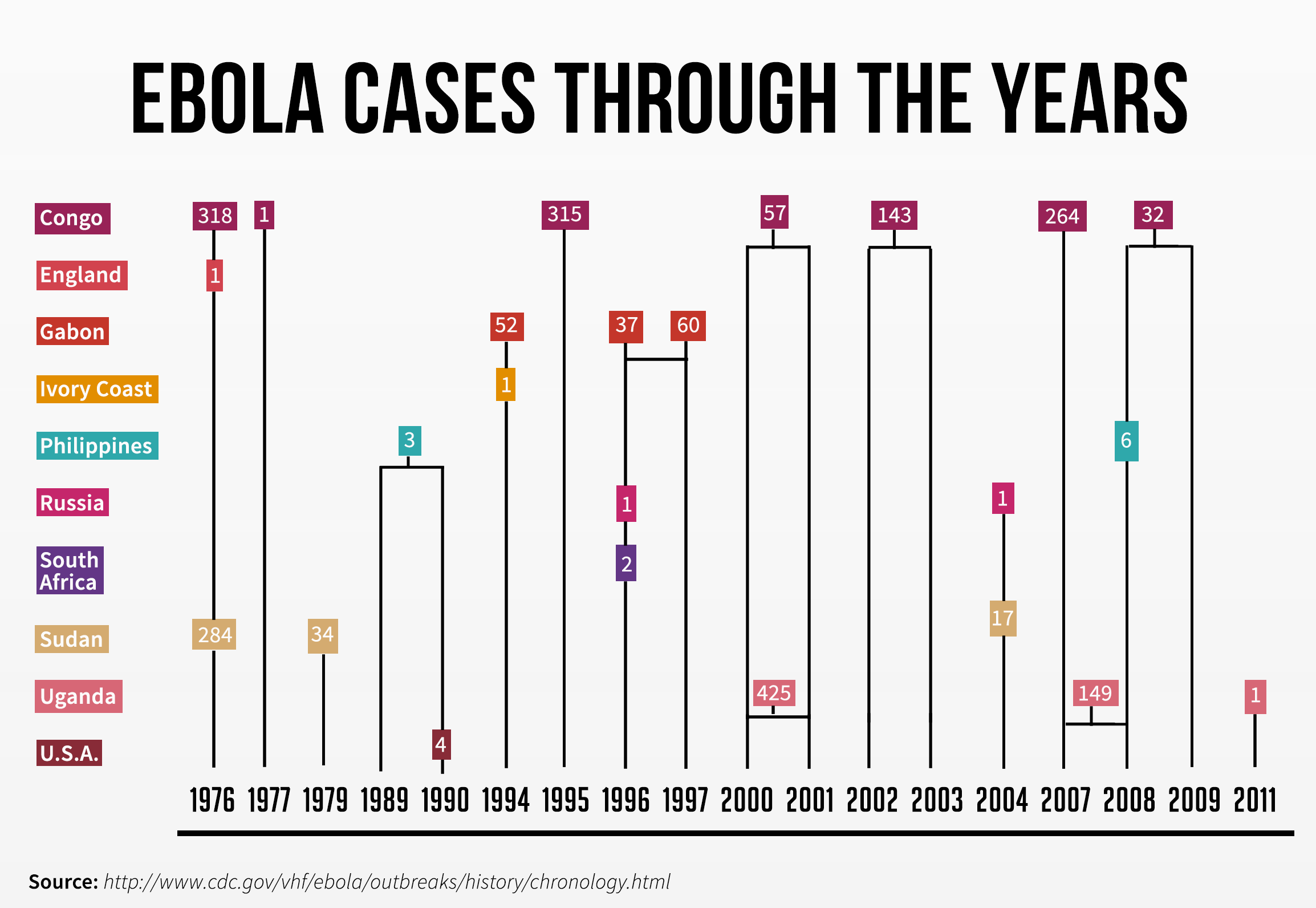

In a span of one year, the Ebola virus has killed 7,600 people, exceeding the total number of deaths when it was first identified in 1976 up until 2013, which was recorded at around 1,500.

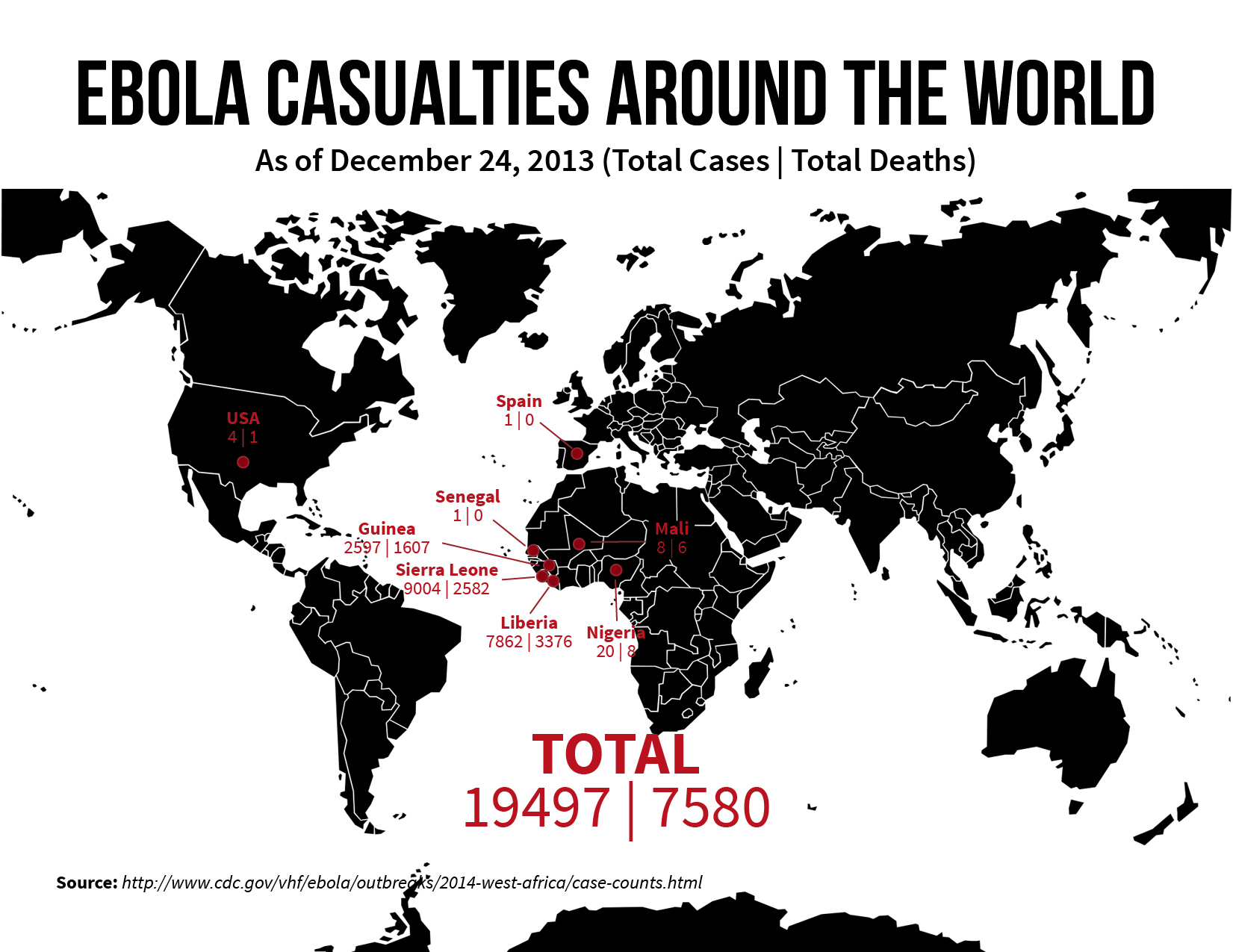

As of Dec. 24, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported a total of 19,563 infected individuals around the world in 2014. Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are the worst-hit countries with 99.5 percent share of total case counts. Cases which originated in the West Africa outbreak were also reported in Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, United States and Mali.

Another Ebola virus outbreak, unrelated to the one in West Africa, also occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 66 reported cases and 49 reported deaths. However, the country has been considered Ebola-free since Nov. 21 after the last Ebola case showed negative results after two tests.

Contagion

The Ebola virus disease is a viral, fatal illness transmitted through direct contact with the bodily fluids of an infected individual. It becomes infectious after appearance of symptoms, which takes two to 21 days to develop.

The Ebola crisis have resulted to death and suffering in West Africa; rapidly destroying lives, decimating communities and orphaning children. The closing down of businesses, disruption of farming and markets slowed the country’s economic growth, affecting the income and livelihood of millions of people.

Meanwhile, the government budget of affected areas also experienced pressure, as their ability in providing basic services was limited.

Relief

West Africa, for instance, needed help beyond what its government could provide, prompting many international associations, charitable organizations, foundations and individuals to provide monetary donations and other forms of assistance.

The World Health Organization (WHO) announced collaboration with health ministries from 11 countries of West Africa to build a strategy in coordinating technical support in July 2014. In late August, they issued a roadmap for scaled-up response to guide and coordinate international response and prevent further spread within six to nine months.

As the outbreak was declared a “threat to international peace and security” by the United Nations Security Council in September 2014, the body unanimously adopted Resolution 2177 which urged UN members to help and provide more resources for the combat.

Moreover, World Food Programme (WFP) has distributed food to more than 1.7 million people in the three most affected countries. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) responded by creating Ebola Community Care Centers, restoring basic social services including child and maternal health and nutrition services, water and sanitation, child protection, education and social welfare.

Shortfall

Several nations have also assisted to combat the spread of Ebola. United States, for one, has sent thousands of troops in affected countries and has pledged $1 billion assistance funds.

However, the overall effort of Asian countries to assist in combating the crisis is still not enough, said World Bank president Jim Yong Ki in a news conference in November 2014.

Though these countries pledged and helped through giving monetary donations and sending medical equipment and health workers, their contribution is still small compared to their overall capacity to assist, he said.

In addition, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors Without Borders) criticized in their press release the global effort to fight the epidemic in West Africa for being “slow and uneven.”

Though all three worst-hit countries have received support in terms of financing and building facilities, the actual or hands-on work are left to non-governmental organizations (NGOs), local authorities and health workers who lack required expertise, the report said.

Exposed to the same dilemma, local doctors and nurses were also afraid to come to work. According to the WHO, the mandatory quarantine discouraged them from volunteering for the Ebola duty.

These Ebola health workers, however, have been named 2014 Persons of the Year by Time Magazine, dubbing them as “the ones who answered the call.”

Prevention

Because of the virus’ threat, many countries across the world have implemented actions to prevent the spread of Ebola into their area, such as releasing advisory notices to warn travelers of the risks of going to affected countries.

Precautionary measures, such as isolation facilities, training of staff, bio-containment exercises, and health screening for incoming travelers, have also been implemented by many countries. Some withhold the visas of visitors from affected countries, closed borders, cancelled flights and restricted ships arriving to seaports.

In the Philippines, the Department of Health declared the country “Ebola-free” on Nov. 15, assuring that the 133 Filipino UN peacekeepers who served in Ebola-stricken West Africa were screened negative. One of them who had experienced chilling and high fever during their 21-day quarantine in Caballo Island was only diagnosed with malaria.