By Florence May Jose and Charry Espino

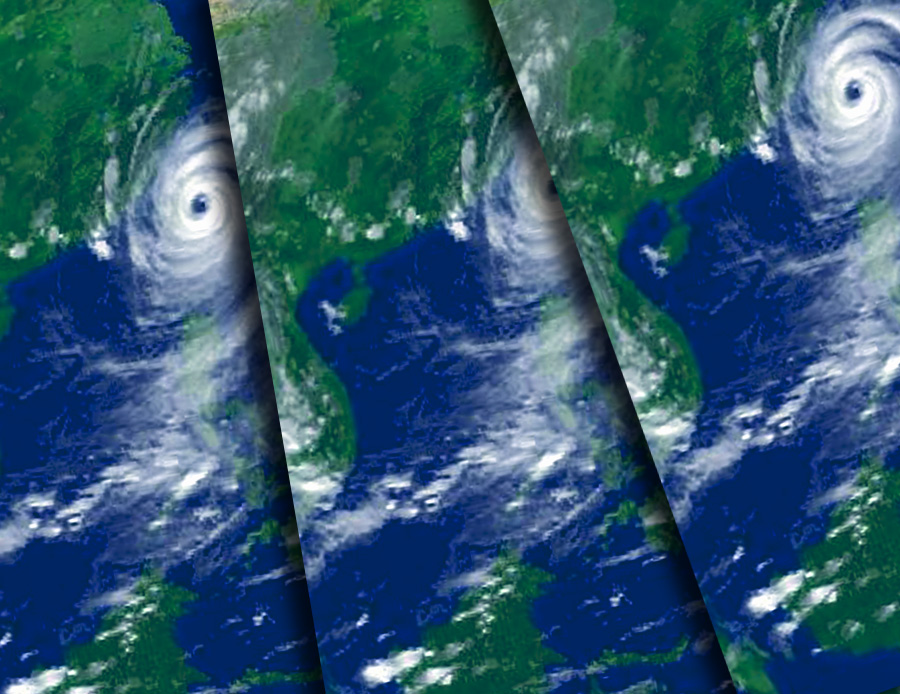

20 typhoons in a year. A dozen sizable earthquakes annually. A handful of active volcanos. Filipinos live at the mercy of the elements. The catch: we’re not ready to deal with them, ever.

The onset of the last four months of the year — commonly known to Filipinos as the –ber months — can only mean two things: the beginning of the long Christmas holidays, and readying for the wet weather that it brings. In the past few years, however, there has been a noticeable trend of particularly strong typhoons hitting the country just as people begin to prepare for the yearend festivities.

Given the repeated avowals of the government and its long-winded National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) to mitigate the impact of perennial weather-related disasters, massive flooding and storm-related deaths still mar Christmas for millions of families across the country.

Worse, natural disasters do not choose when to strike. Our calendar as a nation in the Pacific – smack in the middle of the world’s typhoon, earthquake, and volcano belts – is filled with deadly calamities that happen with cold regularity. As if locked in a perpetual battle against the forces of nature, the inhabitants of these 7,107 islands continually find themselves clinging ever more desperately to life in one of the most disaster-prone regions in the world.

A disaster with no name

It was mid-August when a calamity with storm-like features brought heavy flooding to the streets of Metro Manila. The nameless storm, later identified as a particularly prolonged Southwest Monsoon (Habagat in Filipino), caused havoc to millions because of the massive volume of water that it dumped over much of Luzon, reminding many of the destruction brought about by Tropical Storm Ondoy (international codename Ketsana) back in 2009. The incessant rain and the widespread flooding it caused left more than a hundred people dead and almost Php3.01 billion in property and infrastructure damages in the affected areas. Subsequent reports indicate the mid-year Habagat as having brought roughly 80% of the water volume that Ondoy released, even surpassing the rainfall records set by the 2009 tropical storm.

A major difference between last year’s floods and those from three years ago was the introduction of the Department of Science and Technology’s web-based meteorological project National Operational Assessment of Hazards – Project NOAH, for short – as well as the new color-coded rainfall and flood warning system of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). These advances enabled many residents in high-risk areas to evacuate to safer ground. It also enabled netizens to direct rescue efforts to specific locations with the help of social media. However, initial confusion over the new PAGASA warning systems, as well as the sheer scale of the Habagat event, contributed to difficulties in subsequent rescue, relief, and retrieval operations across the affected regions.

“We used to be typhoon-free”

Nearly a year after Typhoon Sendong (international codename Washi) lashed northern Mindanao and portions of Visayas, another more powerful storm cut a huge path of destruction across much of southern Philippines.

Super Typhoon Pablo (international codename Bopha) was the most destructive storm to have hit the country in 2012. Before making landfall on the eastern coast of Mindanao, the US Joint Typhoon Warning Center reported that the storm packed maximum sustained winds of 259 kph, with gusts of up to 314 kph. In addition, updates from Project NOAH at the height of the storm indicate that Pablo dumped as much as 80 mm of rain per hour – well above the rainfall rates of Sendong (50 mm/hour) and Ondoy (56.83 mm/hour). It is the latest of only four super typhoons to hit Mindanao, and is the most southerly of any storm to have hit the country.

According to the NDRRMC, as of Christmas last year, 6.2 million people had been affected in 34 provinces in Visayas and Mindanao, while the death toll stood at 1,067, with 2,666 injured and 834 still missing.

Also as of Christmas last year, total cost of damages due to Pablo stood at a staggering Php36.9 billion – with damage to agriculture accounting for Php26.5 billion or roughly three-fourths of all damages sustained. This is due to the fact that hard-hit areas in the Davao and Central Mindanao regions were occupied by large swaths of plantation lands dedicated to prime cash crops for export.

Pablo left Davao Oriental – which, together with Compostella Valley, bore the full brunt of the super typhoon – with more than three hundred dead. Ironically, the province had won regional and national awards for disaster preparedness. Reports from the province in the wake of the storm revealed that designated evacuation centers did not withstand the sheer force that Pablo packed. Residents also did not recall receiving official evacuation orders from the provincial government. Davao Oriental Gov. Corazon Malanyaon, who in August 2012 had received the Gawad Kalasag for heading the Best Prepared Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council in the region, was quoted in the Inquirer as saying that despite her province’s readiness, “the force of Typhoon Pablo was simply overwhelming.”

“We used to be typhoon-free. That’s no longer the case now. In rebuilding our houses, we really have to make sure [they are] built to withstand super typhoons,” Malanyaon said.

Solidarity with victims

Helping Pablo’s victims to stand up from their harrowing ordeal has become a national endeavor, with donations from thousands of concerned citizens and institutions pouring in from across the country. Media networks have led in calling out for donations and volunteers, putting aside their usually fierce competition in order to serve those in need.

For its part, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) has provided Family Access Cards (FACs), which also help in determining the type of services and interventions they need.

The Manila Standard Today reported that the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) had made Php3.9 billion worth of emergency loans available for members affected by super typhoon Pablo.

In an Inquirer report, the National Democratic Front (NDF) declared a 26-day ceasefire from Dec. 20, 2012 until January 15, 2013 to give way for relief operations they were conducting in typhoon-ravaged areas. NDF also deferred festivities marking the 44th founding anniversary of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in solidarity with the people of Davao Oriental and Compostela Valley.

Other countries pitched in the relief efforts in Mindanao. Indonesia donated 2,000 metric tons of rice, while Canada sent Can$3 million (Php120 million) in aid to the victims of Pablo through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the International Committee of the Red Cross and Oxfam Canada to ensure the welfare of the survivors. Australia provided Aus$7.3 million (Php307 million) to victims of typhoon Pablo which was divided for food, shelter, health supplies and other needs of the affected families. American troops stationed in Mindanao also joined in the relief and rescue operations, partnering with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in conducting post-disaster missions in towns made inaccessible by damaged bridges and blocked roads.

We have seen this same solidarity with disaster victims many times before. In the aftermath of the Habagat floods in August and well into September last year, students in UP and many other universities sprang into action, collecting and packing relief goods and going out into severely affected communities to distribute them. Experience has shown that the Filipino is always ready to lend a helping hand to those affected by calamities. Curiously, these displays of mass voluntarism in the aftermath of major disasters have not been seen in the areas of disaster preparedness and mitigation. The closest we’ve come to public participation in disaster preparations are through online calls to evacuate or get ready for impending calamities, as well as with a handful of community-based volunteer organizations that compliment local disaster response units.

Aid not being distributed

While the rest of the nation was able to celebrate Christmas and New Year, and despite the millions of dollars in foreign aid money pouring into the disaster zone, survivors still have had to beg for food and water from passersby. Things got so desperate that by mid-January this year, thousands of residents from towns hardest-hit by Pablo had barricaded themselves along a major road passing through much of devastated Compostella Valley, to protest what they saw as the unjust appropriation of relief goods to survivors and their families.

The barricaders, led by the Barug Katawhan alliance of people’s organizations, have accused the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) of hoarding relief goods and conniving with the AFP in appropriating those relief goods for counter-insurgency purposes. There are also reports that aid packs are being sold for as much as PhP200, as well as of some survivors receiving spoiled rice. For its part, the DSWD has denied the accusations. Welfare Secretary Dinky Soliman herself has promised the distribution of 10,000 sacks of rice by the end of January.

By the end of February, however, the situation has only worsened. Things got to a head when hundreds of protesters broke into the DSWD Regional Office in Davao City and seized thousands of kilos of rice being stored there. Public opinion has been divided on the incident, with some arguing whether or not the victims’ circumstances justify their actions. But the incident more clearly underlines the fact that state efforts to mitigate the humanitarian crisis spawned by Super Typhoon Pablo have been failing, and that the survivors are facing what essentially is state negligence of their plight.

Beyond reaction

The technology exists for us to be able to track down killer storms or record earthquakes and predict which seismic faults are primed to produce them, or where tsunamis might strike. The task now is to get the science out of the monitoring stations and into every Filipino household. It is now not enough to know how to interpret government-issued warnings; we ourselves should be made fully aware of the science behind the prevention of natural disasters. It will take a combination of strengthening disaster education within the basic curriculum of Filipino schools, and a sustained and long-term effort by media companies to raise the scientific consciousness of all Filipino viewers, readers, and listeners regarding disaster preparedness.

Finally, the suggestions above can only happen if these are backed up by the government. This, however, doesn’t absolve the state of the need to improve its capacity to deal with natural disasters. President Aquino has to get serious with disaster preparedness, particularly with our capacity to respond to massive flooding and typhoons. The Philippines has a Geohazard Map that Local Government Units can use in drawing up strict zoning regulations in high-risk areas. The Coast Guard has to be strengthened and capacitated to become first responders during floods and storms. The government has to lead in the training and regular deployment of millions of disaster “reservists” – people whom the state can tap whenever it needs more manpower to help during calamities of massive scope. Government policy regarding disaster response must be geared towards the prevention of deaths and damages, while at the same time building and strengthening its own capacity to mitigate the effects.

The natural calamities that befall the country every year serve as a constant reminder that it may be more fun in the Philippines, but life here sure is dangerous. If we are to continue living in our little violent corner of the world, we must re-evaluate the way we look at natural disasters. The typhoons and earthquakes that buffet our existence aren’t things that we could wish away; they’ve been shaping the land for hundreds of millions of years, and we’re all just squatting on their handiwork. We have to be prepared to live with the consequences.

(photo credits: newsinfo.inquirer.net, www.csmonitor.com, balitangporkilo.wordpress.com, soyprinsipe.blogspot.com, mackyramirez.wordpress.com)